Overview

This project aims to implement and build a deeper level of understanding in Neural Networks. This article will profile how they learn just like the human brain does. Much of what you will see in this project is based on the first two chapters of the text by Michael Nielsen titled Neural Networks and Deep Learning. While Nielsen builds neural network that is capable of classifying handwritten digits in Python (2.7), I’ll show you how we can do it in R for a special sort of challenge.

To follow along or see the data, you can download from my repository on Github, which also includes the R script to load the data and build the Neural Network. What will follow will be two-fold: 1) a tl;dr version of what a Neural Network is and how it works; 2) an implementation in R for those who may want to learn how to do it in this language. For those unfamiliar with statistics, calculus, and data science, the first part of this article will be valuable to your understanding what Neural Networks are and how they work. That being said, the second part of this article should be valuable to those who are ready to dip their feet into the world of data science. With that out of the way, let’s get started.

How do Neural Networks, work?

At a high level, Neural Networks are just that, a model of how your neurons work in your brain. The difference here is that it’s an emulation of your brain in a computer (not as scary as it sounds). The idea is that if you were shown the number 5 right now, your eyes would register the number, pass that information to your brain where certain neurons would fire based on the image. Then, your brain would determine that it is a 5 you are seeing.

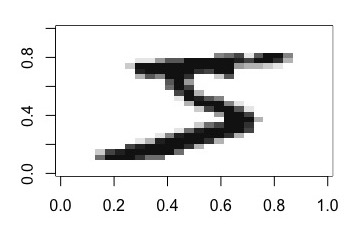

In order to do this in a computer, we introduce a few equivalents to model what happens in the human brain. For this project, we are taking a large dataset of handwritten digits. Each digit comprises of 784 pixels, and looks like this:

Each pixel represents an input, and each pixel is given a grayscale number, meaning a white pixel is 0, and a darker pixel is a number representing how dark the pixel is.

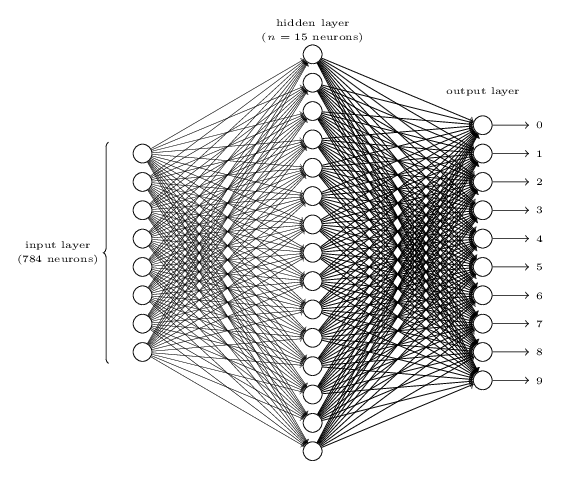

So, we input 784 values. These values are weighted (weights are learned through training data) and passed to the next layer of the network. A network and its layers look like this:

Each of the 784 input values is sent to each of the nodes in the middle (hidden) layer. What I mean by this is that one pixel value is sent to each of the 30 nodes in the hidden layer. In our case, this represents a 784 by 30 matrix as you’ll see we use 30 nodes in the hidden layer. You’ll also notice 10 nodes in what is called the output layer. Each of these nodes represents a final determination of the handwritten digit being 0 through 9.

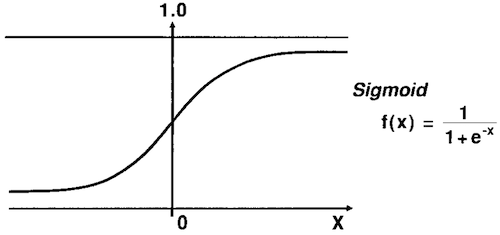

Let’s talk through how one pixel (input) would pass through the entire network after having been weighted and passed to the middle (hidden) layer. From here, the new, weighted value is input into the middle layer. The node in the middle layer takes the value and runs it through what is called an activation function. In our case, we’ll use a Sigmoid function which looks like this:

In R, our now weighted input is passed into the below function as z:

| |

So what does the Activation (Sigmoid) function do? In laymen’s terms, it determines if the input is of value. You’ll see what this means in the next paragraph.

From here, the output of the Sigmoid function is weighted and passed as input into the final layer of 10 nodes (remember: representing each of the 10 digits 0 through 9). That input is ran through the Activation function again, and the neural network outputs a vector of ten values, like this:

| |

These values represent how much the neural network “thinks” the handwritten inputted image is each number. We simply take the highest output (closest to 1) and consider the neural network to have classified the digit as that value. This output is from an untrained network, but it makes logical sense that the network thinks an 8 and 3 look similar. In this case, we’d say the network predicts that the handwritten image is a 3!

The key points to remember of how a network classifies a digit are: edges weight the inputs, nodes determine if those weighted inputs are of value, the values at the nodes are passed on to be weighted and valued again until the output layer is reached. The output tells us what the input should be classified as.

Implementing NN in R

Now that we’ve briefly walked through what steps a network takes to classify a handwritten digit, we must walk through how we train the network to get good at classifying digits correctly. Let’s try to do this while also showcasing some of the code to be implemented in R.

To train a network, we must give it some data so it can learn. We do this by splitting the dataset. If you’ve studied statistical modeling in any capacity, you’ll likely be familiar with this practice. In our handwritten image dataset we have 70,000 images, so we’ll feed our network 60,000 images to learn from and 10,000 to test on. The primary difference between the “learning” and “testing” digits is that in the learning phase we are able to adjust the weights and biases such that it gets more digits right. This is done through a reduction in what is called a cost function.

Stochastic Gradient Descent

To start, we begin with the Stochastic Gradient Descent function. The cost function I referenced above? Gradient descent is a fancy way of saying we minimize the cost function (i.e. minimize how many digit classifications we get wrong). We want to minimize cost because cost represents how poorly our network classifies digits. The higher the cost, the worse our network classifies digits correctly.

The stochastic portion of Stochastic Gradient Descent references the fact that we are estimating gradient descent.

We estimate the gradient descent because in order to train our neural network, we will utilize a process called mini batching. We use mini batching for a number of reasons; the main reasons being that we can train our network using a much smaller amount of computing power (this is by far not a complete answer).

To begin building this learning part of our network, we must split the training data out into mini-batches of size 10 (meaning each mini batch has 10 handwritten images in it). In R, this is how we’ll do it.

| |

We create a nested list of 6000 mini batches, each of size mini.batch.size = 10.

Now, we feed each mini batch through our neural network and calculate weights and biases such that it will classify the mini batch correctly. So, we build a for loop to iterate through each mini batch, and call a new function update.mini.batch.

Update Mini Batch

Within this function, we instantiate an empty list for the weights and biases. We iterate through each observation in the mini batch, feeding the gradient values (how dark a pixel is) as x and the actual handwritten digit (0 thru 9) as y.

| |

You’ll notice above we call our backpropagation function. Read on to see what this does.

Backpropagation

In laymens terms, backpropagation takes the observations of a mini batch and determines the weights and biases for each observation that will correctly classify the digits in the mini batch. That’s a mouth full, but this is how our network improves its classification ability. We will adjust our weights and biases for each observation in the mini batch. The reason it is called backpropagation is because through mathematical proofs, we can show how to efficiently calculate the gradient (or cost function) through each layer going backwards from the output layer. I will try to save the mathematical speak for Michael Nielsen, who explains it in detail here.

To implement in R, we initialize our weights and biases (remember: these are on the edges in the network) and a list of the activations at each node. To start, these activations are just our inputs (784 grey scale pixel values). We feed these values forward first, calculating what our current network would classify this digit as. All of this is done in the following code:

| |

To help you understand where we are- we’ve just taken one observation; ran it through our network; calculated the weight on each edge; and calculated the activation at each node. Now is where we backpropagate. This means we determine the weights in which we will classify the digit correctly. We estimate this through the gradient of our cost function, meaning we attempt to minimize the chance our network missclassifies the digit.

| |

This calls our cost.derivative function. This function takes our vector of output activations (the list of 10 values between 0 and 1 from earlier), and subtracts 1 from the activation in which our digit actually is. This is important, as this is how our network learns. We take this vector of activations and calculate our output error (by multiplying by the derivative of our activation function).

| |

To close, we calculate our weights and biases that feed into our output layer, such that we get the digit classification right (or as close as we can get it). Based on these weights and biases, we can calculate the changes necessary to the weights and biases in the layer behind too. This, in essence, is backpropagation. We return a list of the weights and biases that, given the inputs we just gave the network, would classify the digit correctly. This is done in the code below:

| |

The backpropagate function will be called each time as it iterates through each observation in the mini batch.

Finish Update Mini Batch

After we’ve calculated the weights and biases that would best classify each digit in our mini batch, we come back out of the backpropagation function and finish up updating our network. We take the weights and biases (of which we have a different set for each observation in the mini batch) and we edit the current weights and biases of the network. These edits are made based on what would be necessary to correctly classify the entire mini batch we just backpropagated, with a suppressing factor called the learning rate (or eta).

To touch on the learning rate briefly, it influences the extent of which we can change the current weights and biases of the network. This change is based on what would best classify the mini batch we just backpropagated. Without a learning rate, we may completely jump over our optimal weights and biases for which our network does the best at classifying all digits, not just the digits in a mini batch.

Taking a step out…

So at a high-level, we’ve done the following thus far:

- Split our training data into batches of 10

- Backpropagated to determine the weights and biases for which our network would best classify each handwritten digit in the mini batch correctly

- Updated the weights and biases of our network to best classify based on the mini batch it has just been trained on

To finish training the network, we simply have to set up a for loop to do everything we’ve talked about up to this point. For each mini batch, we update the weights and biases of the network to better classify digits. Remember, we had a dataset of 60,000 digits, with batch sizes of only 10 digits, so we’ll iterate many times. Once we’ve done that, we can evaluate our network on our testing data. If we’ve done everything right, we should have well tuned weights and biases that should classify images of handwritten digits at 50% accuracy.

Epochs

You read that right! 50% accuracy. That’s because I forgot to mention, once we’ve tuned the weights and biases over each mini batch we’ve only completed one epoch. Remember the learning rate I talked about earlier? Instead of loosening things up and running the risk of our network getting worse over time, we have to do an epoch a number of times so our network can incrementally improve towards optimality. This means we keep the weights and biases of the network, randomly split our data into mini batches, backpropagate over each mini batch, and update weights all over again.

Ideally, once we’ve tuned our network’s weights over a number of epochs, we could begin using our network to classify digits in real time. Think along the lines of banks automating the processing of checks. Kind of cool, right?

In Closing

If you’ve made it this far, congratulations. I hope you’ve learned a little bit about how neural networks are implemented and how they learn. If you’d like to try it our for yourself, see the source code. There are a number of helper functions that I didn’t go over for the sake of brevity, so be sure to familiarize yourself with those too. Otherwise, leave a comment and let me know what you thought of this project!